Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

@Celi-Folia: You should look into AAVE, which does have a 'ser'-'estar' distinction.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Firstly, answers to the exercises:

Let me know of any errors.

Portāre and vehere are near synonyms. Both have the meanings of 'bear, carry, convey' as do a couple of other verbs, but vehere is special as in the passive voice it can mean 'to ride' as in on a horse or car or boat, which isn't too great a leap from 'to be borne'.

Also are these lessons good so far? Any suggestions?

Lēctiō Trēs

Neuter Gender

The neuter gender is simply another gender, not too much to say about it. As we only know two cases and only in the singular, it's quite easy to describe. The key ending is -um. In the second declension it has the same form in the nominative as in the accusative, and the same form as the masculine nouns (mulus nouns) accusative: vīnum - 'wine' is both its nominative and its accusative. Some example sentences: Paulus vīnum amat - 'Paul loves wine' and vīnum est onerōsum - wine is heavy. Some more neuter nouns are: monastērium - 'monastery', ōvum - 'egg', oppidum - 'town' and oleum - 'oil'.

More Notes on Nouns

So far we have seen two cases: the nominative and the accusative. The nominative is simple in Latin as it is always used simply as the subject of a sentence, except that it is also used in copula predicates such as monachus est fessus - 'the monk is tired' or discipulī sunt - they are students. (This sentence has a few new things in it; they will all be explained soon, promise.)

The accusative case's most simple use is that of the direct object. We have already seen plenty of sentences like this such as our first Latin sentence: mūlus silvam spectat. It also has a few other adverbial uses: to indicate duration: multōs annōs - 'for many years'; and to indicate direction towards: domum - 'homewards'.

The accusative was also used in some exclamations, a good one being mē miserum - 'woe is me, o wretched me'. Note that if you are a female you will probably want to say mē miseram. In classical times it was also used as the subject of an indirect clause but this was replaced soon after. Don't worry too much about this.

Lastly, the accusative can also be used with specific prepositions when motion is involved: per - 'through', ad - 'to', trans - 'across' and in when it has the specific meaning of 'into, onto'. If you just want to say 'in, on' rather than convey a sense of motion, you must use the ablative! In can mean both in and on, so don't be surpised when you see something like 'the bag was in the mule'.

The Ablative

The ablative conveys 'in, on, with, by or from'. It has a lot of uses in Latin, most of them being adverbial in nature: magnā celeritāte is literally 'with great speed' but could equally validly be translated as 'very quickly'. We will look at its various uses later on but for now just know that it is a merger of the PIE ablative, locative and instrumental cases and retains the uses of all three.

Sometimes prepositions govern the ablative case; cum - 'with (strictly in the comitative sense)', in - 'in, on', ab* - 'from, by' and ēx* - 'out of, away from, off'. *These last two are only required in this form before a vowel (and I think before h as well), and when followed by a consonant they usually become ā and ē. There aren't any rules as to when, but I will just use them before any non-h consonant. Keep in mind that ā means 'from' and not 'to' as one familiar with other Romance languages might think, especially in a text without long vowels marked.

The endings for the ablative of mulus nouns and vinum nouns is both -ō in the singular and for silva nouns it is -ā. So for example, mūlus in silvā ambulat, et Paulus in mūlō sedet - 'the mule walks in the forest, and Paul sits on the mule.'

Misc.

In the sentence Paulus cum mūlus in silvā ambulat, mūlus is in the accusative because it is also taking part in walking. In this sentence the focus is Paul and the fact that he's walking with the mule is more of a comment. Thes sentences means a similar thing but doesn't focus on Paul: Paulus et mūlus in silvā ambulant and Paulus mūlusque in silvā ambulant - 'Paul and the mule walk in the forest.' You will have noticed that there is an extra 'n' in the verb; this is because we have plural subjects and the verb must then be plural too! For all of the verbs you have learnt so far, making them plural is as easy as adding that little 'n'.

With one exception: the plural of est is sunt. One more grammar point that might be obvious: when there is no explicit subject, it is implied in the verb. So we have fessus est - 'he/she/it is tired' and discipulī sunt - 'they are students'.

I think this lesson is getting sort of long so I will leave the plural to the next lesson. Should I do genitive and vocative as well or would you rather I look more at verb conjugations? Also there wasn't a lot of vocab this lesson so expect a lot in the next one.

Exercises

Remember there are no vowel lengths marked. Translate the following sentences:

- Paulus monachus est.

- Sarcina in mulo est.

- Paulus sarcinam non portat.

- In sarcina sunt vinum et cibus.

And these:

- The mule doesn't sit on Paul.

- Not Paul but the mule carries the wine and the oil. (but = sed)

- Paul and the mule carry the bag.

- Paul is walking from the town through the wood to the monastery.

Spoiler:

Portāre and vehere are near synonyms. Both have the meanings of 'bear, carry, convey' as do a couple of other verbs, but vehere is special as in the passive voice it can mean 'to ride' as in on a horse or car or boat, which isn't too great a leap from 'to be borne'.

Also are these lessons good so far? Any suggestions?

Lēctiō Trēs

Neuter Gender

The neuter gender is simply another gender, not too much to say about it. As we only know two cases and only in the singular, it's quite easy to describe. The key ending is -um. In the second declension it has the same form in the nominative as in the accusative, and the same form as the masculine nouns (mulus nouns) accusative: vīnum - 'wine' is both its nominative and its accusative. Some example sentences: Paulus vīnum amat - 'Paul loves wine' and vīnum est onerōsum - wine is heavy. Some more neuter nouns are: monastērium - 'monastery', ōvum - 'egg', oppidum - 'town' and oleum - 'oil'.

More Notes on Nouns

So far we have seen two cases: the nominative and the accusative. The nominative is simple in Latin as it is always used simply as the subject of a sentence, except that it is also used in copula predicates such as monachus est fessus - 'the monk is tired' or discipulī sunt - they are students. (This sentence has a few new things in it; they will all be explained soon, promise.)

The accusative case's most simple use is that of the direct object. We have already seen plenty of sentences like this such as our first Latin sentence: mūlus silvam spectat. It also has a few other adverbial uses: to indicate duration: multōs annōs - 'for many years'; and to indicate direction towards: domum - 'homewards'.

The accusative was also used in some exclamations, a good one being mē miserum - 'woe is me, o wretched me'. Note that if you are a female you will probably want to say mē miseram. In classical times it was also used as the subject of an indirect clause but this was replaced soon after. Don't worry too much about this.

Lastly, the accusative can also be used with specific prepositions when motion is involved: per - 'through', ad - 'to', trans - 'across' and in when it has the specific meaning of 'into, onto'. If you just want to say 'in, on' rather than convey a sense of motion, you must use the ablative! In can mean both in and on, so don't be surpised when you see something like 'the bag was in the mule'.

The Ablative

The ablative conveys 'in, on, with, by or from'. It has a lot of uses in Latin, most of them being adverbial in nature: magnā celeritāte is literally 'with great speed' but could equally validly be translated as 'very quickly'. We will look at its various uses later on but for now just know that it is a merger of the PIE ablative, locative and instrumental cases and retains the uses of all three.

Sometimes prepositions govern the ablative case; cum - 'with (strictly in the comitative sense)', in - 'in, on', ab* - 'from, by' and ēx* - 'out of, away from, off'. *These last two are only required in this form before a vowel (and I think before h as well), and when followed by a consonant they usually become ā and ē. There aren't any rules as to when, but I will just use them before any non-h consonant. Keep in mind that ā means 'from' and not 'to' as one familiar with other Romance languages might think, especially in a text without long vowels marked.

The endings for the ablative of mulus nouns and vinum nouns is both -ō in the singular and for silva nouns it is -ā. So for example, mūlus in silvā ambulat, et Paulus in mūlō sedet - 'the mule walks in the forest, and Paul sits on the mule.'

Misc.

In the sentence Paulus cum mūlus in silvā ambulat, mūlus is in the accusative because it is also taking part in walking. In this sentence the focus is Paul and the fact that he's walking with the mule is more of a comment. Thes sentences means a similar thing but doesn't focus on Paul: Paulus et mūlus in silvā ambulant and Paulus mūlusque in silvā ambulant - 'Paul and the mule walk in the forest.' You will have noticed that there is an extra 'n' in the verb; this is because we have plural subjects and the verb must then be plural too! For all of the verbs you have learnt so far, making them plural is as easy as adding that little 'n'.

With one exception: the plural of est is sunt. One more grammar point that might be obvious: when there is no explicit subject, it is implied in the verb. So we have fessus est - 'he/she/it is tired' and discipulī sunt - 'they are students'.

I think this lesson is getting sort of long so I will leave the plural to the next lesson. Should I do genitive and vocative as well or would you rather I look more at verb conjugations? Also there wasn't a lot of vocab this lesson so expect a lot in the next one.

Exercises

Remember there are no vowel lengths marked. Translate the following sentences:

- Paulus monachus est.

- Sarcina in mulo est.

- Paulus sarcinam non portat.

- In sarcina sunt vinum et cibus.

And these:

- The mule doesn't sit on Paul.

- Not Paul but the mule carries the wine and the oil. (but = sed)

- Paul and the mule carry the bag.

- Paul is walking from the town through the wood to the monastery.

Last edited by kanejam on 03 Jul 2013 00:46, edited 2 times in total.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

***Important***

I missed the fact that the negative particle is actually nōn, rather than *non. I apologise but I blame the people who don't mark long vowels! I will go through and change it in the morning.

I missed the fact that the negative particle is actually nōn, rather than *non. I apologise but I blame the people who don't mark long vowels! I will go through and change it in the morning.

Last edited by kanejam on 03 Jul 2013 23:06, edited 1 time in total.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

That's just so Sanskrit. (carati '(he) walks' c.s. caranti '(they) walk'). And the appropriate forms of 'to be' are 'asti' and 'santi' -- it should be easy to guess which one is plural! And the case endings we covered so far are a lot like Sanskrit as well:as easy as adding that little 'n'.

masculine: -ah in nominative, -am in accusative

feminine: -ā in nominative, -ām in accusative

neuter: -am in both nominative and accusative

And some of the vocabulary items (nōn sedet ~ na sīdati, -que ~ -ca, ...) I know the two languages are related, but these words are just way too similar (even Greek doesn't have that -n- in the plural).

Spoiler:

I'd prefer to do verb conjugations (and pronouns) first. And I'd like the vocab tabulated, so I can refer to it easily.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Are you familiar with a lot of Sanskrit and Greek? Latin should be a breeze for you thenAmbrisio wrote:That's just so Sanskrit. (carati '(he) walks' c.s. caranti '(they) walk'). And the appropriate forms of 'to be' are 'asti' and 'santi' -- it should be easy to guess which one is plural! And the case endings we covered so far are a lot like Sanskrit as well:as easy as adding that little 'n'.

masculine: -ah in nominative, -am in accusative

feminine: -ā in nominative, -ām in accusative

neuter: -am in both nominative and accusative

And some of the vocabulary items (nōn sedet ~ na sīdati, -que ~ -ca, ...) I know the two languages are related, but these words are just way too similar (even Greek doesn't have that -n- in the plural).

Gosh how many languages do you know? Yeah I don't like referring to 'second declension masculine', and saying 'mulus nouns' is much easier to remember.Ambrisio wrote:I like the names 'mūlus nouns' and 'vīnum nouns'. They're much easier to remember than 'first declension masculine' and '3.14th declension aquatic'! Personally, that's how I learned Estonian inflections, which can be extremely irregular.Spoiler:

I'd prefer to do verb conjugations (and pronouns) first. And I'd like the vocab tabulated, so I can refer to it easily.

Anyway, your exercises are all correct except the third part of the second exercise should be portant, as both Paul and the mule are doing the carrying, thus the verb should be plural. Otherwise all correct! I'm not actually sure about et/-que. -que is only really used for single words, so to join large phrases or clauses you will want to use et. But in that particular sentence I would have accepted either. Et also has another use: Et Paulus et mūlus per silvam ambulant - 'both Paul and the mule are walking through the forest. So you see et ... et ... - 'both ... and ...' and note that this can be used for more than just two things so it does not necessarily mean 'both'.

Okay, what do you mean by tabulate? phpBB can't do tables can it? Would just a clear list with a line break after each entry do? Otherwise you are happy with the lessons? I will get to work on the next lesson then: plurals and verb conjugations.

I'm not sure if they publish in LatinSo could you say "In sarcinā est Cibus Et Vīnum", with a singular verb?

Edit: Here is all the vocab learnt so far:

Spoiler:

Last edited by kanejam on 03 Jul 2013 14:12, edited 1 time in total.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

I've attended a spoken Sanskrit immersion program once--even though I'm not too pleased with the way they modernize the language (I've never seen their interrogative particle 'vā' in any Sanskrit texts; 'api' or 'kim' at the beginning of the sentence feels better. I also hate the T-V distinction they artificially introduced into the language! In classical Sanskrit, even God is addressed with what they consider an informal pronoun, 'tvam' -- cognate to 'tū', as in 'Tē Deum Laudāmus'). It's kind of like how the Dies Irae is pronounced in settings of the Requiem Mass. "Dies ire, dies illa" -- it's just horrible (I hate listening to Requiems for that very reason). Choir singers don't have any problem with the 'ae' sound, do they?

I love classical languages, and have always wanted to learn Latin and Hebrew.

And how would you use 'et ... et ...' when there are three or more subjects? Would it be 'Et Paulus, et Petrus, et Maria in silvā ambulant'? Or would it just be better to say 'Paulus, Petrus et Maria' as in English?

I like the vocab list. Except for the spelling of 'monastērium', of course! I'd also like to have the infinitive form beside each verb (so amāre, ambulāre, ...)

I love classical languages, and have always wanted to learn Latin and Hebrew.

So it's like 'vel ... vel ...' or 'aut ... aut ...'. How would you say 'neither ... nor ...'?et ... et ... - 'both ... and ...'

And how would you use 'et ... et ...' when there are three or more subjects? Would it be 'Et Paulus, et Petrus, et Maria in silvā ambulant'? Or would it just be better to say 'Paulus, Petrus et Maria' as in English?

I like the vocab list. Except for the spelling of 'monastērium', of course! I'd also like to have the infinitive form beside each verb (so amāre, ambulāre, ...)

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Yes! vel is inclusive or, aut is exclusive or. When used in the aut ... aut ... pattern they mean 'either ... or ...'. The word nēque means 'and not, also not' and is a transparent compound of nē, which is an old particle which used to mean 'not' and the -que enclitic. And from here we get nēque ... nēque ... to mean 'neither ... nor ...' and an example of which is: Paulus nēque ambulat nēque sedet - 'Paul neither walks nor sits'.

The trouble with requiems et al. is that they tend to follow ecclesiastic pronunciation, which is a standard cobbled together from all the various medieval pronunciations when everyone spoke Latin as they spoke their own language. The clear analogue is how English speakers butcher Latin words, especially Law terms e.g. subpoena [səˈpiːnə] which in Latin is pronounced /sup'pojna/ and means 'under penalty'.

I love Latin for the diachronics. With just about every lexical item you find, there are cognates in the other ancient PIE languages or reflexes or reborrowings in each daughter language. Sometimes the links are clear but a lot of the time that isn't so.

Lēctiō Quattuor

Noun Plurals

Have a look at this sentence: mūlī silvam spectant - 'the mules watch the forest'. Notice that our mūlus has been joined by his friends and so the word mūlus is now in the plural as mūlī. Also note that the verb is in the plural because it agrees in number with its subject. -ī is in fact the nominative plural for all regular mulus nouns. The accusative ending is -ōs: silva mūlōs spectat - 'the forest watches the mules'.

The mulus nouns' plural ablative form is -īs, but this is easy to remember as it is in fact the plural ablative ending for silva nouns and vinum nouns as well! Here's an example sentence: monachī in mūlīs sedent - 'the monks sit on (the) mules'.

The nominative plural ending for silva nouns is -ae: sarcinae in mūlō sunt - 'the bags are on the mule'. For the accusative the ending is -ās: mūlus sarcinās portat - 'the mule carries the bags'. As mentioned above, the ablative is -īs: cibus in sarcinīs est - 'the food is in the bags'.

The nominative plural ending for vinum nouns is -a. Note this is the same as the nominative singular for silva nouns. And once again the nominative plural is the same as the accusative plural. Examples: mūlus vīna portat; vīna in sarcinās sunt - 'the mule carries the wines; the wines are in the bags'. The ablative is again -īs: 'monachī in monastēriīs habitant' - monks live in monasteries.

Just as an interesting side note, look at the noun endings again. In the Eastern Romance languages the plural comes from the nominative, cf. Italian -i < -ī in the masculine, -e < -ae in the feminine and -a in the neuter. In the Western Romance languages the plurals came from the accusative, cf. Spanish -os < -ōs in the masculine and -as < -ās in the feminine.

Verbs

So far we have seen only a few verbs: amat, ambulat, est, habitat ('live', which I just introduced earlier), portat, sedet, and spectat. These are all in the third person singular (3SG). To be exact, and to give you an idea of how deep the verbal rabbit hole is, they are in the finite active indicative non-perfect present third person singular. But don't get too worried by that! I will introduce the new paradigms very slowly.

Usually the most common reference form is the infinitive. This is not the case in Latin; the reference form will be the 1st person present singular. The ending for the first person present in almost every single verb is -ō. So our verbs again in their main reference form are: amō, ambulō, sum, habitō, portō, sedeō and spectō. The only verb we know that doesn't follow this is sum. There are very, very, very few verbs that don't follow this.

Have another look at the third person forms above. Here are the same verbs in the infinitive: amāre, ambulāre, esse, habitāre, portāre, sedēre and spectāre. For all of them but esse (which doesn't belong to a conjugation at all), the vowel before the -re is the thematic vowel and shows which conjugation the verb is. Note that they have the same vowel as the vowel before the -t in the third person forms. All of them are -āre verbs except sedō which is an -ēre verb.

There are four conjugations: -āre verbs which are the most common and the most regular, -ēre verbs, -ere verbs which are the most irregular (in my mind at least), and -īre such as audiō/audīre - 'I hear/to hear'. The thematic vowel is usually lost in the first person singular (amō) and shortened in the third person singular (amat).

To get the second person singular, add an -s without shortening the vowel. Here are our verbs in second person: amās, ambulās, audīs, es, habitās, portās, sedēs and spectās. Of course as you might have guessed, esse is irregular. For completeness, the 1st person plural ending is pretty much always -mus and -tis with no vowel shortening.

The full reference form for a Latin verb will give four things: firstly the 1st person present, then the infinitive, then the 1st person perfect and then the supine, which is a sort of non-finite impersonal form thingy. Here is a full verb: amō, amāre, amāvī, amātum. Don't worry about the last two, we will cover them in due course. Also, so far we've focussed on the first conjugation (-āre verbs) and not everything that we've studied applies to every verb. Namely, don't worry about the plurals in the other conjugations just yet.

Adectives

Just quickly, adjectives in Latin must agree with their head noun both in gender and number, but also in case. The good news is that for most adjectives, the feminine endings are exactly the same as the silva nouns endings, the masculine the same as the mulus nouns and the neuter the same as the vinum nouns. So Paulus fessus mūlōs fessōs in silvā fessā spectat - 'tired Paul watches tired mules in a tired forest'.

These adjectives are first and second declension adjectives. There are also third declension adjectives, but they are a bit funkier. We will cover those after we third declension nouns. Also, most first/second declension adjectives can be made into adverbs and a lot of them are formed by replacing the ending with -ē.

Exercises

Firstly, new vocab:

Next a reading exercise. You don't have to reply to this or anything, just read it and make sure you understand everything (remember, there are no long vowels):

Paulus et Benedictus monachi sunt. In monasterio habitant. Benedictus presbyter est, et cum ancillis in culina laborat. Paulus non presbyter sed discipulus est. In culina et in bibliotheca laborat. Benedictus, ubi cibum vinumque desiderat, Paulum ad oppidum mittit. Paulus igitur vinum in oppido emit et ex oppido ad monasterium cum mulo ambulat. Mulus lente sarcinae onerosae portant; sarcinae vino et ovis et oleo et unguentis onerosae sunt. Mulus est fessus, et Paulus etiam est fessus.

The same text with vowel lengths:

Translate the following:

- I am Mark (Marcus) and you are Lucy (Lucia).

- You (to a group of women) are tired and heavy.

- You are sitting on a mule, we are walking to the monastery and the monks are working in the kitchen.

- When they are at town, they always want wine.

- The maids live in the library with the students and the tired monks.

Translate the following:

- In silva ambulat.

- In silvam ambulat.

- Monachus in cucullo clamat.

- Lucia et Marcus in mulis fessis sedent.

- Neque silvam neque sarcinas mulus amat.

Give a full declination of the three cases you know so far for these three nouns: unguentum onerōsum, mūlus fessus and bibliothēca umbrōsa.

Next lesson we will cover some pronouns, questions and maybe the genitive and some more verb forms.

The trouble with requiems et al. is that they tend to follow ecclesiastic pronunciation, which is a standard cobbled together from all the various medieval pronunciations when everyone spoke Latin as they spoke their own language. The clear analogue is how English speakers butcher Latin words, especially Law terms e.g. subpoena [səˈpiːnə] which in Latin is pronounced /sup'pojna/ and means 'under penalty'.

I love Latin for the diachronics. With just about every lexical item you find, there are cognates in the other ancient PIE languages or reflexes or reborrowings in each daughter language. Sometimes the links are clear but a lot of the time that isn't so.

Lēctiō Quattuor

Noun Plurals

Have a look at this sentence: mūlī silvam spectant - 'the mules watch the forest'. Notice that our mūlus has been joined by his friends and so the word mūlus is now in the plural as mūlī. Also note that the verb is in the plural because it agrees in number with its subject. -ī is in fact the nominative plural for all regular mulus nouns. The accusative ending is -ōs: silva mūlōs spectat - 'the forest watches the mules'.

The mulus nouns' plural ablative form is -īs, but this is easy to remember as it is in fact the plural ablative ending for silva nouns and vinum nouns as well! Here's an example sentence: monachī in mūlīs sedent - 'the monks sit on (the) mules'.

The nominative plural ending for silva nouns is -ae: sarcinae in mūlō sunt - 'the bags are on the mule'. For the accusative the ending is -ās: mūlus sarcinās portat - 'the mule carries the bags'. As mentioned above, the ablative is -īs: cibus in sarcinīs est - 'the food is in the bags'.

The nominative plural ending for vinum nouns is -a. Note this is the same as the nominative singular for silva nouns. And once again the nominative plural is the same as the accusative plural. Examples: mūlus vīna portat; vīna in sarcinās sunt - 'the mule carries the wines; the wines are in the bags'. The ablative is again -īs: 'monachī in monastēriīs habitant' - monks live in monasteries.

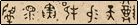

Code: Select all

|silva nouns|mulus nouns|vinum nouns

_______|__f._1st___|__m._2nd___|__n._2nd___

nom. | -ae | -ī | -a

acc. | -ās | -ōs | -a

abl. | -īs | -īs | -īs

Verbs

So far we have seen only a few verbs: amat, ambulat, est, habitat ('live', which I just introduced earlier), portat, sedet, and spectat. These are all in the third person singular (3SG). To be exact, and to give you an idea of how deep the verbal rabbit hole is, they are in the finite active indicative non-perfect present third person singular. But don't get too worried by that! I will introduce the new paradigms very slowly.

Usually the most common reference form is the infinitive. This is not the case in Latin; the reference form will be the 1st person present singular. The ending for the first person present in almost every single verb is -ō. So our verbs again in their main reference form are: amō, ambulō, sum, habitō, portō, sedeō and spectō. The only verb we know that doesn't follow this is sum. There are very, very, very few verbs that don't follow this.

Have another look at the third person forms above. Here are the same verbs in the infinitive: amāre, ambulāre, esse, habitāre, portāre, sedēre and spectāre. For all of them but esse (which doesn't belong to a conjugation at all), the vowel before the -re is the thematic vowel and shows which conjugation the verb is. Note that they have the same vowel as the vowel before the -t in the third person forms. All of them are -āre verbs except sedō which is an -ēre verb.

There are four conjugations: -āre verbs which are the most common and the most regular, -ēre verbs, -ere verbs which are the most irregular (in my mind at least), and -īre such as audiō/audīre - 'I hear/to hear'. The thematic vowel is usually lost in the first person singular (amō) and shortened in the third person singular (amat).

To get the second person singular, add an -s without shortening the vowel. Here are our verbs in second person: amās, ambulās, audīs, es, habitās, portās, sedēs and spectās. Of course as you might have guessed, esse is irregular. For completeness, the 1st person plural ending is pretty much always -mus and -tis with no vowel shortening.

The full reference form for a Latin verb will give four things: firstly the 1st person present, then the infinitive, then the 1st person perfect and then the supine, which is a sort of non-finite impersonal form thingy. Here is a full verb: amō, amāre, amāvī, amātum. Don't worry about the last two, we will cover them in due course. Also, so far we've focussed on the first conjugation (-āre verbs) and not everything that we've studied applies to every verb. Namely, don't worry about the plurals in the other conjugations just yet.

Adectives

Just quickly, adjectives in Latin must agree with their head noun both in gender and number, but also in case. The good news is that for most adjectives, the feminine endings are exactly the same as the silva nouns endings, the masculine the same as the mulus nouns and the neuter the same as the vinum nouns. So Paulus fessus mūlōs fessōs in silvā fessā spectat - 'tired Paul watches tired mules in a tired forest'.

These adjectives are first and second declension adjectives. There are also third declension adjectives, but they are a bit funkier. We will cover those after we third declension nouns. Also, most first/second declension adjectives can be made into adverbs and a lot of them are formed by replacing the ending with -ē.

Exercises

Firstly, new vocab:

Spoiler:

Paulus et Benedictus monachi sunt. In monasterio habitant. Benedictus presbyter est, et cum ancillis in culina laborat. Paulus non presbyter sed discipulus est. In culina et in bibliotheca laborat. Benedictus, ubi cibum vinumque desiderat, Paulum ad oppidum mittit. Paulus igitur vinum in oppido emit et ex oppido ad monasterium cum mulo ambulat. Mulus lente sarcinae onerosae portant; sarcinae vino et ovis et oleo et unguentis onerosae sunt. Mulus est fessus, et Paulus etiam est fessus.

The same text with vowel lengths:

Spoiler:

- I am Mark (Marcus) and you are Lucy (Lucia).

- You (to a group of women) are tired and heavy.

- You are sitting on a mule, we are walking to the monastery and the monks are working in the kitchen.

- When they are at town, they always want wine.

- The maids live in the library with the students and the tired monks.

Translate the following:

- In silva ambulat.

- In silvam ambulat.

- Monachus in cucullo clamat.

- Lucia et Marcus in mulis fessis sedent.

- Neque silvam neque sarcinas mulus amat.

Give a full declination of the three cases you know so far for these three nouns: unguentum onerōsum, mūlus fessus and bibliothēca umbrōsa.

Next lesson we will cover some pronouns, questions and maybe the genitive and some more verb forms.

Last edited by kanejam on 04 Jul 2013 00:16, edited 2 times in total.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Cave cave, amice, et festina lente! I think you mean negative particle.kanejam wrote: negative participle

I'm not sure that would work with a masculine (albeit inanimate) + neuter subject.Ambrisio wrote:yes,as easy as adding that little 'n'...

but these words are just way too similar (even Greek doesn't have that -n- in the plural).does, sort of.

In Attic, the -n- disappears in the PRS.3PL, but not without making a compensatory lengthening of the -o-.

*[ba.l:õn.ti] < *[ba.lõn.si] < *[ba.lō.si] < βάλλουσι

A similar process happened with the PRS.PTCP.F which ends in -ousa, but used to end in something like *-ontja.

*[ba.l:õn.tja] < *[ba.lõn.sja] < *[ba.lō.sa] < βάλλουσα

In some Ancientdialects, though, the -n- did not disappear in these positions.

Doric*βάλλοντι

So could you say "In sarcinā est Cibus Et Vīnum", with a singular verb?

I don't know if

http://linguistlist.org/issues/6/6-59.html

These esteemed folks think not. Singular verbs with neuter plural subjects appear to be a fossilization from PIE times, that was already giving way in Classical

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Indeed.Celi-Folia wrote:That's right, Vulgar Latin (i.e. the spoken language) had some innovations that didn't exist in the classical (written) language:Ambrisio wrote:It's kind of interesting that Latin lacks many grammatical features that I expected from a Romance language (no T-V, no 'ser'-'estar', strict SVO ordering except when the object is a pronoun ...) So do those features derive from Vulgar Latin, perhaps?

> I've heard that the T-V distinction dates back to the fourth century AD and the plural vos was used to signify authority, according to Brown and Gilman in "The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity"

> The ser-estar distinction differs between Romance language, where in Italian and Occitan for instance, the cognate of stāre is much less common than in Spanish, and while Old French had the distinction the two merged into one in modern French. But how it started, I'm not totally sure..

> The loss of case marking may have made freedom of word order less feasible so the SVO word order dominates because the subject comes first and the verb separates it from the object, if SOV were default then the subject and object would be more difficult to distinguish. Of course, with object pronouns there's little opportunity for confusion between subject and object so the SOV order can be retained in that case.

Classical Latin is an Italic, not a Romance language.

I would bet good denarii that it's related to the pluralis maiestatis. When it first reared its head, who knows exactly, but as soon as someone acts with the authority of a group, (or acts as if (s)he were that group), those that believe and have faith would begin making a T-V distinction.I've heard that the T-V distinction dates back to the fourth century AD and the plural vos was used to signify authority, according to Brown and Gilman in "The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity"

It's interesting to consider howThe ser-estar distinction differs between Romance language, where in Italian and Occitan for instance, the cognate of stāre is much less common than in Spanish, and while Old French had the distinction the two merged into one in modern French. But how it started, I'm not totally sure.

How it started? Well, in English we have phrases like "How does that stand with you?", "This does not sit well with me", "My knowledge of Latin will always stand in good stead with me". Now, of course,

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

@ Celi-Folia

I imagine stāre began to evolve as a copula from a locatival (here I am right now) perspective.

Just looking at some hits from the Vulgata.

What’s the difference in meaning between

duo viri steterunt secus illas (Lk 24:4)

Two men stood apart from them

Two men were apart from them

Et steterunt super pedes suos (Rev 11:11)

And they stood up on their feet

And they were up on their feet

et nautæ, et qui in mari operantur, longe steterunt (Rev 18:17)

And the sailors, and those who work in the sea, stood a long way off

And the sailors, and those who work in the sea, were a long way off

ecce mater ejus et fratres stabant foras, quærentes loqui ei. (Mt 12:46)

Look! His mom and siblings were standing outside, seeking to talk to him.

Look! His mom and siblings were outside, seeking to talk to him.

et omnis turba stabat in littore, (Mt 13:2)

And the whole crowd was standing on the shore

And the whole crowd was on the shore

Et post pusillum accesserunt qui stabant, et dixerunt Petro : Vere et tu ex illis es : (Mt 26:73)

And a little while later the ones who were standing around arrived and they said to Peter: Hey, you really are one of them

And a little while later the ones who happened to be there arrived , and they said to Peter: Hey, you really are one of them

Stabant autem principes sacerdotum et scribæ constanter accusantes eum (Lk 23:10)

However the chief priests and the scribes were standing (there) harassing him

However the chief priests and the scribes were (there) harassing him

***{¿¿An ancient grand-uncle to estar + gerundio?? You be the judge}

Somehow, this reminds me of the semantic overlap in a sentence like fui a la tienda

sentence like fui a la tienda

which could be either

I went to the store. OR I was at the store.

![Tick [tick]](./images/smilies/tickic.png)

![:) [:)]](./images/smilies/icon_smile2.png)

I imagine stāre began to evolve as a copula from a locatival (here I am right now) perspective.

Just looking at some hits from the Vulgata.

What’s the difference in meaning between

duo viri steterunt secus illas (Lk 24:4)

Two men stood apart from them

Two men were apart from them

Et steterunt super pedes suos (Rev 11:11)

And they stood up on their feet

And they were up on their feet

et nautæ, et qui in mari operantur, longe steterunt (Rev 18:17)

And the sailors, and those who work in the sea, stood a long way off

And the sailors, and those who work in the sea, were a long way off

ecce mater ejus et fratres stabant foras, quærentes loqui ei. (Mt 12:46)

Look! His mom and siblings were standing outside, seeking to talk to him.

Look! His mom and siblings were outside, seeking to talk to him.

et omnis turba stabat in littore, (Mt 13:2)

And the whole crowd was standing on the shore

And the whole crowd was on the shore

Et post pusillum accesserunt qui stabant, et dixerunt Petro : Vere et tu ex illis es : (Mt 26:73)

And a little while later the ones who were standing around arrived and they said to Peter: Hey, you really are one of them

And a little while later the ones who happened to be there arrived , and they said to Peter: Hey, you really are one of them

Stabant autem principes sacerdotum et scribæ constanter accusantes eum (Lk 23:10)

However the chief priests and the scribes were standing (there) harassing him

However the chief priests and the scribes were (there) harassing him

***{¿¿An ancient grand-uncle to estar + gerundio?? You be the judge}

Somehow, this reminds me of the semantic overlap in a

which could be either

I went to the store. OR I was at the store.

How are my lessons?

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Another possibility is that the ser / estar distinction was created, or at least reinforced, by the Basque substrate inLambuzhao wrote:It's interesting to consider howdoes not have the full-blown, two headed copula like

ser/estar, while

hybridized them in the lab. And this is just three Romance sisters. esse/stāre did not become the duovir in every Romance dialect's copula-kingdom.

How it started? Well, in English we have phrases like "How does that stand with you?", "This does not sit well with me", "My knowledge of Latin will always stand in good stead with me". Now, of course,is a language distantly related to English. I'll check some lit for any parallels.

Quite goodHow are my lessons?

Երկնէր երկին, երկնէր երկիր, երկնէր և ծովն ծիրանի.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

What a way to describe the Latin ending -t!finite active indicative non-perfect present third person singular

Spoiler:

In 'Mūlus est fessus, et Paulus etiam est fessus.' do I have to use the word 'fessus' twice?

How would I say 'Paul is not a priest but his disciple, who works in both the kitchen and the library'?

Sounds poetic!in silvā fessā

Spoiler:

Is it like the Estonian supine (also called the "ma infinitive", or in Estonian, "ma-tegevusnimi"), which is used after certain verbs (hakkama 'start', pidama 'have to', ...) instead of the infinitive? The same form is used in Finnish, c.f.supine

which in modern Finnish, is "lähden laulamaan" or "I'm going to sing".Kalevala wrote:Lähteäni laulamahan

Then what does 'ergo' mean, as in 'Te ergo quaesumus'?igitur

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Interesting! I know there are a lot of parallels between Latin and Greek, especially in the first and second declension and conjugations.Lambuzhao wrote:yes,does, sort of.

That's still doesn't really explain why it popped up though, why not address people in third person to be polite, as in Italian?Lambuzhao wrote:I would bet good denarii that it's related to the pluralis maiestatis. When it first reared its head, who knows exactly, but as soon as someone acts with the authority of a group, (or acts as if (s)he were that group), those that believe and have faith would begin making a T-V distinction.

You are right about the difference between the two is very small. Do you know whether it was explicitly meant as a second copula, or more figuratively as we in English use verbs like stand and sit? The Vulgate is 4th century, written by a Roman so it could well be a very real influence from St Jerome's spoken language creeping in to his writing. There are certainly other non-classical constructions used in it.Lambuzhao wrote:Just looking at some hits from the Vulgata.

Aha!Lambuzhao wrote:... ejus ...

Lambuzhao wrote:![Tick [tick]](./images/smilies/tickic.png)

![:) [:)]](./images/smilies/icon_smile2.png)

Aww, shucks guysatman wrote:Quite good ! Keep them coming!

Anyway, on with the lessons:

Spoiler:

Remember that discipulus in Latin means 'student' although it is where we get the word disciple from. In the reading text the line Paulus non presbyter sed discipulus est does not imply that Paulus is Benedict's student, rather that he is just a student in general, and could be someone else's student. To say 'Paul is not a priest but his disciple' you need the genitive construction, which I will introduce in the very next lesson. It would look like this: Paulus non presbyter sed discipulus Benedictī est. For now don't worry about using things like 'who'.Ambrisio wrote:In 'Mūlus est fessus, et Paulus etiam est fessus.' do I have to use the word 'fessus' twice?

How would I say 'Paul is not a priest but his disciple, who works in both the kitchen and the library'?

Spoiler:

Yeah I think the supine is like that; to be completely honest I'm not entirely comfortable with it yet. Ergō also means 'thus', but more of a logical conclusion type thing, 'consequently, because of this' such as the famous cōgitō ergō sum. Ergō can also be used as an adverb and on top of 'consequently, accordingly' it can mean 'precisely'.Ambrisio wrote:Is it like the Estonian supine (also called the "ma infinitive", or in Estonian, "ma-tegevusnimi"), which is used after certain verbs (hakkama 'start', pidama 'have to', ...) instead of the infinitive? The same form is used in Finnish, c.f.supinewhich in modern Finnish, is "lähden laulamaan" or "I'm going to sing".Kalevala wrote:Lähteäni laulamahan

Then what does 'ergo' mean, as in 'Te ergo quaesumus'?igitur

Edit: @Ambrisio, was there any reason you missed the third exercise? (the declining one)

Last edited by kanejam on 04 Jul 2013 02:12, edited 1 time in total.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

No problem. I just overlooked it.

And do all adjectives decline like mūlus/silva/vīnum? Also, I think we should go over some more declensions before we get to the genitive case.

Spoiler:

So what are the third person pronouns (he, she, it, they) in Latin?'Heus' clāmat monachus in cucullō (notice the long vowel!)

And do all adjectives decline like mūlus/silva/vīnum? Also, I think we should go over some more declensions before we get to the genitive case.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Sweet, you declined them all perfectly. Yes, I missed that long vowel sorry. Fixed it now though! I forgot to mention; the sentences would have worked with the pronouns but that adds a strong emphasis on them, cf. doing the same thing in Italian or Spanish.Ambrisio wrote:No problem. I just overlooked it.

Spoiler:So what are the third person pronouns (he, she, it, they) in Latin? And do all adjectives decline like mūlus/silva/vīnum? Also, I think we should go over some more declensions before we get to the genitive case.'Heus' clāmat monachus in cucullō (notice the long vowel!)

Latin does have proper third person but sometimes the demonstratives are used as third person pronouns. The difference between the two can change the meaning of a sentence. I will put a section on pronouns in the next lesson. If you want to look them up yourself and in more detail than I'm going to into them, look at this wikibooks lesson on Latin pronouns.

I'll put -er nouns into the next lesson as well then, and then we will have covered the first two declensions completely. I want to cover genitives before we cover any more declensions though

Edit: I forgot to mention that, no, not all adjectives are first/second declension. There are third declension nouns that roughly follow third declension nouns (but no fourth or fifth declension adjectives). From the next lesson onwards I will be calling the first/second declension adjectives bonus adjectives.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Lēctiō Quīnque

Vocative

For every single noun, apart from a few Greek loans and the second declension masculine nouns (mulus nouns) in the singular, the vocative is the same as the nominative. Don't worry about the Greek nouns, but for the mulus nouns the vocative singular ending is just -e: et tū Brūte? - 'you too, Brutus?'.

It often occurs with ō, a particle meanin 'o/oh' as in ō diē - 'oh gods!'. It might also occur behind other simple interjections such as eho - 'eh, hey, look here': eho tū - 'hey you'.

First Declension

The good news is that you have basically learnt the entire first declension. Just in case case you forgot, these are the silva nouns. As you know, almost all the silva nouns are feminine. There are a handful, usually professions, that decline exactly as the silva nouns but are in fact masculine. Two examples are pīrāta - 'pirate' and poēta - 'poet'. There are a few more but we won't worry about them.

Latin also has a lot of Greek words in it. Those of you familiar with classical history will know that the Romans ripped of a lot of Greek culture, including their architecture, laws and religion. So it makes sense that they also took a lot of words. In educated circles they often retained much of their endings, but you will definitely see Greek nouns declined as if they were completely regular Latin words.

The Greek words that belong to the first declension end in -ē, -ēs and-ās in the nominative singular. They might be masculine or feminine. Most of their declension is the same as the silva nouns (which, along with historical reasons is why they are placed in the same category), and whatever isn't the same often becomes similar through analogy. In any case you won't need to worry about these for a long while, and so for all intents and purposes you know the entire first declension.

The last thing to learn about silva nouns is that they have an alternate ablative plural form. Because the ablative plural is -īs in silva nouns as well as mulus and vinum nouns, there is the potential to get confused between words of different genders which have the same stem. Examples of this are equus - 'horse' and equa - 'mare', fīlius - 'son' and fīlia - 'daughter'.

When there is no ambiguity, the simple ending -īs is used, however with these pairs there might be confusion, and in specific cases, the ending -ābus is used instead. With some nouns, like fīlia and dea - 'goddess', (cf. deus - 'god'), the forms fīliābus and deābus are much more common than the -īs forms.

Second Declension

You also know most of the second declension already. There are a few Greek loans in this declension, but try are much closer to their Latin equivalents. The Greek endings simply have -os instead of -us and -on instead of -um, and otherwise decline exactly as mulus nouns for the masculine loans and vinum nouns for the neuter loans. Often the words are completely assimilated and it would be the people educated in Greek who would retain the endings.

There is one last thing about mulus nouns before we move on to the rest of the second declension: nouns whose stems end in -i such as fīlius (stem fīli-), the vocative ending will fuse with the -i, so that the vocative is fīlī.

We have two more nouns to learn in the second declension. Don't worry though because they are very easy. We met one of them before: presbyter - 'priest' which ends is masculine and ends in -er. However, apart from the nominative singular and the vocative singular it behaves like a mulus noun. So the plural nominative is presbyterī, the accusative singular is presbyterum etc. Just think of it as a mulus noun that is simply missing its -us and its -e. This is the same as puer - 'boy', and so I will be calling these nouns puer nouns.

Some nouns ending in -er in the nominative and vocative singulars lose that -e- when they decline. An example of this is ager - 'field', which in the accusative becomes agrum. Because they lose their -e-, they are often just called r-stems, to distinguish from the er-stems like puer. For this course though they will be referred to as ager nouns. Both ager nouns and puer nouns are still masculine and so adjectives will simply take their masculine form e.g. puer fessus - 'tired boy', ager umbrōsus - 'dark field', cum presbyterīs territīs - 'with the scared priests'.

Some More Adjectives

Most adjectives are part of the first and second declension; that is they follow the silva nouns' endings in the feminine, the mulus nouns' endings in the masculine and the vinum nouns' endings in the neuter. These will be know as bonus nouns, from the Latin word bonus - 'good'. Some knows belong to the third declension and we will learn them when we learn third declension nouns.

There are also some adjectives that come under this category: miser - 'poor, wretched' follows puer nouns and keeps its er-stem intact when it conjugates e.g. miser mūlus - 'poor mule', miserī mūlī - 'poor mules'. They can also become feminine and neuter, like all adjectives: ancilla misera - 'poor maid' and ovum miserum - 'poor egg'.

And you might have guessed that there will be -er adjectives that lose their -e- when they conjugate e.g. monachus sacer in silvā sacrā ambulat - 'a sacred monk walks in the sacred forest'. Hopefully this is easy to understand. I will call the er-stem adjectives miser adjectives, and the r-stems sacer adjectives.

Adjectives usually follow the noun the modify. However, because of the Latin case endings freeing up the word order, you might see an adjective come before the noun or even be sitting a few words away from it. This is especially prevalent in poetry.

Pronouns

Latin has plenty of personal pronouns because of its gender and case system. Subject pronouns (i.e. nominative pronouns) are used to emphasise, as remember that the person is already encoded in the verb. The first person nominative is ego - 'I' and the second person nominative is tū -'thou'. An example sentence is ego Lucia sum - 'I'm Lucy', but with emphasis, so maybe someone has just called you Egberta or has called someone else Lucy. The plural forms are nōs - 'we, us' and vōs - 'you'.

The accusatives and ablatives of the two first person pronouns are merged: mē - 'me, from me, by me' and tē - 'thee, from thee, by thee'. A common derivative of these are mēcum, tēcum - 'with me, with you'. The accusatives of the plurals are the same as the nominatives, but the ablative is different: nōbīs - 'with us, from us, by us' and vōbīs - 'with you, from you, by you'. There are no vocative cases for the pronouns.

The third person nominative pronouns are is - 'he', ea - 'she' and id - 'it'. If you have ever studied Freud you might recognise the terms Ego and Id, which were the translations for his ideas of Ich and Es. The accusatives are eus - 'him', eam - 'her' and in true neuter fashion id - 'it'. The ablatives are sort of regular on e-: eō - 'by him/it, from him/it' and eā - 'by her, from her'. The plurals are also regular on e-: eī eōs eīs, eae eās eīs, ea ea eīs. The only exception is that you might see iī as well as eī.

There is also a reflexive pronoun. Obviously it has no nominative, and the accusative is the same as the ablative, and is the same in the singular and plural. It's either sē or sēsē. There is very little difference between the two forms except that sēsē is generally used when you want to add emphasis.

Exercises

This lesson got really long, I was also going to cover questions but I suppose that will have to wait to the next lesson with the genitive case.

Vocab:

Translate the following:

- you carry me and I carry thee

- the big bags are on you (pl); we're carrying the small wine, small perfumes and small books

- they (group of women) don't like her because she's lazy (... quod ...)

- Paul and Stephen (Stephanus) work in with fields with the holy master.

- the mule lives in the field with the horses, but doesn't like them.

- the big book in the library is bad

- you are monks

- we are maids and students

- eh boy! eh girl! eh mule! eh egg! eh horses! eh maids!

- they (group of men) also sit

Write 'poor pirate' in Latin in all four cases you know, singular and plural. Then do the same for 'good master', and then 'lazy girl', then 'sacred oil'.

Vocative

For every single noun, apart from a few Greek loans and the second declension masculine nouns (mulus nouns) in the singular, the vocative is the same as the nominative. Don't worry about the Greek nouns, but for the mulus nouns the vocative singular ending is just -e: et tū Brūte? - 'you too, Brutus?'.

It often occurs with ō, a particle meanin 'o/oh' as in ō diē - 'oh gods!'. It might also occur behind other simple interjections such as eho - 'eh, hey, look here': eho tū - 'hey you'.

First Declension

The good news is that you have basically learnt the entire first declension. Just in case case you forgot, these are the silva nouns. As you know, almost all the silva nouns are feminine. There are a handful, usually professions, that decline exactly as the silva nouns but are in fact masculine. Two examples are pīrāta - 'pirate' and poēta - 'poet'. There are a few more but we won't worry about them.

Latin also has a lot of Greek words in it. Those of you familiar with classical history will know that the Romans ripped of a lot of Greek culture, including their architecture, laws and religion. So it makes sense that they also took a lot of words. In educated circles they often retained much of their endings, but you will definitely see Greek nouns declined as if they were completely regular Latin words.

The Greek words that belong to the first declension end in -ē, -ēs and-ās in the nominative singular. They might be masculine or feminine. Most of their declension is the same as the silva nouns (which, along with historical reasons is why they are placed in the same category), and whatever isn't the same often becomes similar through analogy. In any case you won't need to worry about these for a long while, and so for all intents and purposes you know the entire first declension.

The last thing to learn about silva nouns is that they have an alternate ablative plural form. Because the ablative plural is -īs in silva nouns as well as mulus and vinum nouns, there is the potential to get confused between words of different genders which have the same stem. Examples of this are equus - 'horse' and equa - 'mare', fīlius - 'son' and fīlia - 'daughter'.

When there is no ambiguity, the simple ending -īs is used, however with these pairs there might be confusion, and in specific cases, the ending -ābus is used instead. With some nouns, like fīlia and dea - 'goddess', (cf. deus - 'god'), the forms fīliābus and deābus are much more common than the -īs forms.

Second Declension

You also know most of the second declension already. There are a few Greek loans in this declension, but try are much closer to their Latin equivalents. The Greek endings simply have -os instead of -us and -on instead of -um, and otherwise decline exactly as mulus nouns for the masculine loans and vinum nouns for the neuter loans. Often the words are completely assimilated and it would be the people educated in Greek who would retain the endings.

There is one last thing about mulus nouns before we move on to the rest of the second declension: nouns whose stems end in -i such as fīlius (stem fīli-), the vocative ending will fuse with the -i, so that the vocative is fīlī.

We have two more nouns to learn in the second declension. Don't worry though because they are very easy. We met one of them before: presbyter - 'priest' which ends is masculine and ends in -er. However, apart from the nominative singular and the vocative singular it behaves like a mulus noun. So the plural nominative is presbyterī, the accusative singular is presbyterum etc. Just think of it as a mulus noun that is simply missing its -us and its -e. This is the same as puer - 'boy', and so I will be calling these nouns puer nouns.

Some nouns ending in -er in the nominative and vocative singulars lose that -e- when they decline. An example of this is ager - 'field', which in the accusative becomes agrum. Because they lose their -e-, they are often just called r-stems, to distinguish from the er-stems like puer. For this course though they will be referred to as ager nouns. Both ager nouns and puer nouns are still masculine and so adjectives will simply take their masculine form e.g. puer fessus - 'tired boy', ager umbrōsus - 'dark field', cum presbyterīs territīs - 'with the scared priests'.

Some More Adjectives

Most adjectives are part of the first and second declension; that is they follow the silva nouns' endings in the feminine, the mulus nouns' endings in the masculine and the vinum nouns' endings in the neuter. These will be know as bonus nouns, from the Latin word bonus - 'good'. Some knows belong to the third declension and we will learn them when we learn third declension nouns.

There are also some adjectives that come under this category: miser - 'poor, wretched' follows puer nouns and keeps its er-stem intact when it conjugates e.g. miser mūlus - 'poor mule', miserī mūlī - 'poor mules'. They can also become feminine and neuter, like all adjectives: ancilla misera - 'poor maid' and ovum miserum - 'poor egg'.

And you might have guessed that there will be -er adjectives that lose their -e- when they conjugate e.g. monachus sacer in silvā sacrā ambulat - 'a sacred monk walks in the sacred forest'. Hopefully this is easy to understand. I will call the er-stem adjectives miser adjectives, and the r-stems sacer adjectives.

Adjectives usually follow the noun the modify. However, because of the Latin case endings freeing up the word order, you might see an adjective come before the noun or even be sitting a few words away from it. This is especially prevalent in poetry.

Pronouns

Latin has plenty of personal pronouns because of its gender and case system. Subject pronouns (i.e. nominative pronouns) are used to emphasise, as remember that the person is already encoded in the verb. The first person nominative is ego - 'I' and the second person nominative is tū -'thou'. An example sentence is ego Lucia sum - 'I'm Lucy', but with emphasis, so maybe someone has just called you Egberta or has called someone else Lucy. The plural forms are nōs - 'we, us' and vōs - 'you'.

The accusatives and ablatives of the two first person pronouns are merged: mē - 'me, from me, by me' and tē - 'thee, from thee, by thee'. A common derivative of these are mēcum, tēcum - 'with me, with you'. The accusatives of the plurals are the same as the nominatives, but the ablative is different: nōbīs - 'with us, from us, by us' and vōbīs - 'with you, from you, by you'. There are no vocative cases for the pronouns.

The third person nominative pronouns are is - 'he', ea - 'she' and id - 'it'. If you have ever studied Freud you might recognise the terms Ego and Id, which were the translations for his ideas of Ich and Es. The accusatives are eus - 'him', eam - 'her' and in true neuter fashion id - 'it'. The ablatives are sort of regular on e-: eō - 'by him/it, from him/it' and eā - 'by her, from her'. The plurals are also regular on e-: eī eōs eīs, eae eās eīs, ea ea eīs. The only exception is that you might see iī as well as eī.

There is also a reflexive pronoun. Obviously it has no nominative, and the accusative is the same as the ablative, and is the same in the singular and plural. It's either sē or sēsē. There is very little difference between the two forms except that sēsē is generally used when you want to add emphasis.

Exercises

This lesson got really long, I was also going to cover questions but I suppose that will have to wait to the next lesson with the genitive case.

Vocab:

Spoiler:

- you carry me and I carry thee

- the big bags are on you (pl); we're carrying the small wine, small perfumes and small books

- they (group of women) don't like her because she's lazy (... quod ...)

- Paul and Stephen (Stephanus) work in with fields with the holy master.

- the mule lives in the field with the horses, but doesn't like them.

- the big book in the library is bad

- you are monks

- we are maids and students

- eh boy! eh girl! eh mule! eh egg! eh horses! eh maids!

- they (group of men) also sit

Write 'poor pirate' in Latin in all four cases you know, singular and plural. Then do the same for 'good master', and then 'lazy girl', then 'sacred oil'.

Last edited by kanejam on 06 Jul 2013 05:34, edited 5 times in total.

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

The Sanskrit ending is very similar: putrī 'daughter' (related to puella rather than filia) -> putrībhyah. So I think the -īs ending was an innovation.fīliābus

That makes it really easy!The ablatives are sort of regular on e-: eō - 'by him/it, from him/it' and eā - 'by her, from her'. The plurals are also regular on e-: eī eōs eīs, eae eās eīs, ea ea eīs.

Sed nōn cum puellā pulchrā, of course! (And there's another sacer adjective!)monachus sacer in silvā sacrā ambulat

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

Yeah it's sort of like the entire system is regular on e- except for is and id, although there are a few more irregularities in the remaining cases.That makes it really easy!

Exercises are up. I'll start work on the next lesson in the morning (it's nearly 4am

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

All right,

Spoiler:

Re: Lingua Latīna - Lēctiōnēs

There were a few corrections but generally it was very good. The focus of the lessons was agreement of verbs even when they don't have the same endings, and you nailed it. Just one thing: I forgot to say that adjectives follow the nouns they're modelled on in the vocative case; that is, in the masculine singular, bonus nouns take -e e.g. fesse, territe, īgnāve. I also changed three and five slightly as they didn't quite mean what I wanted them to mean, but what you have is definitely correct for both of them.Ambrisio wrote:All right,

Spoiler:

Last edited by kanejam on 06 Jul 2013 05:37, edited 1 time in total.