For now I believe an introduction is in place. The language family finds its earliest ancestor in Proto-Sumro-Letaeric. For this wee introduction I will cannibalise a text I wrote in the introduction for a document I am working on:

The reconstruction of Proto-Sumro-Letaeric (PSL) originally began in 5014AN as an attempt to reconstruct Pre-Proto-Sumro-Naukl using internal reconstruction based off of various allomorphy and stem changes found in Proto-Sumro-Naukl (PSN). At this time linguists were able to reconstruct the lenition of *p *b {*t *d} *k *g *q *s *z to *ɸ *β/∅ *δ *c *ġ *x *ś *ź (a change termed Meocijao's Law after the linguist who proposed it) by observing alternation within certain noun and verb stems. However this reconstruction of Pre-Proto-Sumro-Naukl was a tiny step towards reconstructing PSN's own ancestor.

It wouldn't be until 5036AN that linguists became aware of the relationship between the Letaeric languages and the Sumro-Naukl languages. Previously the connection between these two had gone completely unknown due to how far apart the two families are with the Letaeric languages being spoken in the Makutevnag continent while the Sumro-Naukl languages dominate in Malomanan across the seas. At this time there had been no knowledge of the arrival of the Sumro-Naukl speaking Nebyeto to Malomanan from Makutevnag, so no one ever thought to link the two families together. Indeed the modern languages of each family are so diverse that they barely resemble each other. The connection between the two families was only made when Luabian linguists from Malomanan had been studying the Letaeric languages and reconstructing Proto-Letaeric (PL), eventually publishing their findings. Before publishing their work it was reviewed by Sûttörata, a Werish linguist who had done extensive work reconstructing Proto-Sumro-Naukl. As Sûttörata glazed over the work he was surprised to see some similarities between PSN and PL both in sound correspondences and in morphology. For example the word "ten" was identical in both languages, with both having *peqʷem. Sûttörata quickly went to work attempting to establish a relationship between the two families and he was successful. What was previously an attempt to make Pre-Proto-Sumro-Naukl had now become the reconstruction of Proto-Sumro-Letaeric, estimated to have been spoken around 1000SD (6,000 years before present) somewhere in the north of the Makutevnag continent.

This language family has been quite lucky in that several of it's branches are well attested in the form of early languages being written down, allowing reconstruction work to go back even further than if only the modern languages were the basis for reconstruction. The reconstruction of Proto-Sumro-Letaeric is mostly based off of the reconstructions of Proto-Letaeric and Proto-SUmro-Naukl, both of which had been worked on before the relationship of the two was established. For Proto-Letaeric the main languages used were Old Letaere and Middle Ethei, both languages being the first of their branches to be written (Old Ethei is attested, but not as well as Middle Ethei). When appropriate Wacal (another descendant of Old Ethei) is referred to when information is lacking in Middle Ethei. While there are few Letaeric languages (only two, Ethei and Wacal, are not extinct), their very early attestation and overall morphological conservativeness is invaluable for the reconstruction of Proto-Sumro-Letaeric.

Proto-Sumro-Naukl, by virtue of leaving much more descendants, has more languages used in its reconstruction. The earliest attested languages of the Naukl branch are Ethogiath and Old Naukl, though Ethogiath has a much vaster body of literature to work with despite having went extinct. For the Mangeodge branch the earliest attested language is Old Mangeodge which was used to write an endless amount of texts - Proto-Mangeodge was written but only very scarcely in some inscriptions, even fewer of which have survived. For the Synraspian languages the earliest attested languages are Hajec, Old Tuura and Old Sumrë - the latter of which has the most attestation out of the three by far but has been quite innovative, especially with its nominal morphology, which reduces its importance in reconstruction. Proto-Sumric was written but like Proto-Mangeodge, it was rarely written and very few examples survived especially since the few literate Proto-Sumric speakers wrote on perishable materials. The Sucumian languages have never been written by natives, who to this day don't care about writing, considering it to be silly nonsense. However the ancestors of the two sub-branches of Sucumian languages: Light Sucumian and Dark Sucumian are well recorded in ancient notes and dictionaries written by Old Sumrë speaking shamans. Snippets of Proto-Sucumian exist in the oldest notes, but only mere snippets.

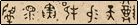

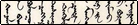

It is also fortunate that these languages were recorded before they had underwent further change. Old Sumrë for example is probably the most innovative, gaining a wealth of new cases and totally reforming its noun gender. Old Sumrë's own daughters would go on to change even more, losing a great deal of the typical Sumro-Letaeric grammar. Meddio for instance lost a vast majority of Old Sumrë's inflection when it became analytic, only to innovate a great variety of new inflections from grammaticalised auxiliaries and pronouns. This is not to mention the drastic sound and grammatical changes that the Mocic languages experienced (cf the Mocic descendants of the Old Sumrë theonym Brumnos:

- West Morish Lainui

- Bawian Bonunots

- Werish Bolwûnuda

- South Luabian Pōwonáz

Now for a quick overview of the language family before finally presenting some juicy details.

Sumro-Letaeric languages

The entire language family, comprising of 90 modern day languages. Far too diverse to list many common features.

Common features:

- Having a paucal number where nouns are distinguished by whether they tend to occur alone or in groups.

- Having a supine verb derived with a velar prefix

Letaeric languages

So far these have not been fleshed out. They are the only branch of the language family to be spoken by descendants of the original Proto-Sumro-Letaeric speakers, the Sumro-Naukl speakers are a different ethnicity that adopted the Proto-Sumro-Letaeric language. Some irony may be found in that the Letaeric language only have two surviving members, while the Sumro-Naukl languages, spoken by people unrelated to the original speakers, have been incredibly successful and numerous. The division of the Letaeric branch and the Sumro-Naukl branch represent the earliest breaking up of Proto-Sumro-Letaeric. Spoken in the Makutevnag continent.

Common features:

- Dislike for word initial and word final vowels

Sumro-Naukl languages

Spoken in Malomanan, with the exception of the Naukl languages, this represents the largest subfamily by far, spoken by originally ethnic Nebyetic peoples.

Naukl languages

Spoken in the Naukl archipelago of the north coast of Makutevnag and consisting of only 2 members; Naukl and Jyztrees, both of which descend from Middle Naukl. There was once a third called Ethogiath, a separate branch of Naukl straight from Proto-Naukl but it was wiped out by Old Naukl.

Mangeodge languages

Spoken in the ancient nation of Meilvarestu. The languages of these heavily agricultural, isolated and militaristic people all descend from Old Mangeodge, which survives as a liturgical language. The West and South subbranches of Mangeodge are spoken in the most ancient heartland of the mangeodge people, with the Mid and North branches developing in their homelands after large migrations into empty nearby lands.

North Mangeodge: North Mainland Mangeodge, Inner & Outer Dawian

Common features

- Heavy Tuuric influence due to trading with Tuuric people. Most evident in the stress accent and system of consonant gradation

Common features

- Presence of the dental fricative θ

- Breaking of /l: r:/ into /gl gr/

Common features

- Debuccalization of fricatives in the coda

- The clusters /sr sl/ becoming /str/

- The affricates /t͡ʃ d͡ʒ/ with /s z/

Common features (the first three are a result of an early West-South sprachbund)

- Debuccalization of fricatives in the coda

- The clusters /sr sl/ becoming /str/

- The affricates /t͡ʃ d͡ʒ/ with /s z/

Spoken by the Sucumi in the Sucumian Isles, a laid back and worriless people, who live off of fishing, whaling and hunting seabirds. This subbranch is split into two main groups: Light Sucumian and Dark Sucumian. These languages are notable for being named with colour terms. The Light Sucumian languages are mostly spoken by fishing communities while Dark Sucumian is spoken by seabird hunters.

Light Sucumian: Red Sucumian, White Sucumian, Silver Sucumian

Common features

- Loss of the dental fricative *δ

Synraspian languages

The largest subgroup, spoken across the entire continent, where many of the different branches have underwent very innovative changes such so that resemblance can be hard to spot for the untrained eye - especially when comparing modern Sumric languages to modern Tuuric ones. This group is distinguished by having Proto-Sumric as the most recent ancestor. It is further broken down into Early Synraspian and Late Synraspian. Early Synraspian is an extinct branch which contained Hajec, spoken by ancient deer herders on the island Gwozhaltasyr before their language and culture was mostly replaced with a Late Synraspian one. Late Synraspian contains Old Tuura and its descendants, plus Old Sumrë and its descendants. Notable for having innovated a system of umlaut.

The descendants of Old Tuura are divided into three branches.

Tundra Tuura: Theukish, Trukian, Dhaulish

Steppe Tuura: Kirudish, Walvian, Tasian

Taiga Tuura: Okiestans, Swarât

Common features

- A system of consonant gradation based on the openness of a syllable

- No voiced plosives

Alatir: Alatir - Spoken by the Alatir who, by a misguided journey, slept for millenia before waking up. As a result their language is much more archaic than the modern languages, having evaded millenia of sound changes.

Lammi: Lammi - Also archaic but only due to dying out and being revived millenia later for politcal purposes.

Naumes: Naumes, Svatolian

Nusibaric: North Nusibara, West Nusibara, East Nusibara - All dialects. Cognates can be tricky to spot in this language thanks to the extensive metathesis and cluster simplification of Old Nusibara.

Middle Sumric: (East Sumric) Chozh, Juakrish, (North-West Sumric) Branjish, West Branjish, (South-West Sumric) Risorese, Meddio

Mocic: A huge dialect continuum stretching from the west coasts to the distant east coast. Undeniably the most innovative branch of the entire language family both phonologically and grammatically. There are too many languages/dialects to list here but they fit into East Mocic, West Mocic, Mid Mocic and Kheldre Mocic.

Apologies for the long wordy post. Now I can begin to post funner etymology posts!