Fortunatian, or Galeco, was a Q-Celtic language spoken throughout the Fortunate Isles1 in the centuries following the fall of the Roman Empire. It was first spread by speakers of Gallaecian who fled after the Roman conquest of northwestern Iberia. They first established themselves in Loicos2, and then expanded outward to several other islands. Written attestations of Fortunatian have been found as far as Cape Verde, where a descendant of the language is still spoken. During the reign of Trajan, several expeditions were sent to Loicos, Neveira3, Llaneja4, and other islands. They were quickly subdued, and incorporated into the Roman Empire as the Fortunate Isles (Latin: Insulae Fortunatae). Due to their distance from the economically prosperous regions of the Roman Empire, not much effort was undertaken to Romanize the pre-existing population. As such, they remained predominantly Celtic-speaking. Those who lived in the Canary Islands coexisted with the Guanches who had already been living there, being influenced by their language & culture as a result. (I want to create a minimalistic descendant of the Guanche language in the same setting. This idea was inspired by my readings on Silbo Gomero, the whistled language spoken on the Canary Islands. Certain people hypothesize that the Guanche language must have had a smaller phonemic inventory due to the limitations of this method of speech, so I’d like to look into that further.)

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the existence of the Fortunate Isles was largely forgotten by the major political powers of Europe, although there was still limited contact between the Isles and Atlantic merchants. As such, the inhabitants of the Fortunate Isles developed independently from their Celtic and Iberian brethren. Given their relative isolation from the rest of the Roman world, the region still maintained religious diversity, being home to adherents of Christianity as well as the Celtic and Guanche pantheons. Fortunatian, as it came to be known, was at its peak between 800 and 1100 AD. By this point, it had experienced a severe reduction in its phonemes, only having 13 consonants and 5 vowels. There are certainly smaller phonologies out there, but I plan to reduce them further when developing the descendants of Fortunatian.

Phonemic Inventory and Orthography

Fortunatian was most commonly written in the Latin script, but the usage of Tifinagh was also seen in the Canary Islands. Both are demonstrated below with the same example sentence.

/m n ŋ/ <m n ng>

/p t k/ <p t c~qu>

/ɸ θ s x/ <f z s g>

/r j w/ <r i~d v~u~b>

/i u e o a/ <i u e o a>

/m n ŋ/ <ⵎ ⵏ ⴳ>

/p t k/ <ⵇ ⵜ ⴽ>

/ɸ θ s x/ <ⴼ ⵝ ⵙ ⵅ>

/r j w/ <ⵕ ⵢ ⵡ>

/i u e o a/ <ⵉ ⵓ ⴻ ⵄ ⴰ>

Toi ti cumes o sin viri.

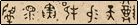

ⵜⵄⵉ ⵜⵕⵉ ⴽⵓⵎⴻⵙ ⵄ ⵙⵉⵏ ⵡⵉⵕⵉ.

be-3S.PRES.IND three dog-MASC.OBL.PLU at DEF man-MASC.NOM.PLU

The man owns three dogs. (Three dogs are at the man.)

Diachronic History:

Proto-Celtic to Gallaecian

1. Here, the Fortunate Isles refers to the Canary Islands and the Azores.

2. ATL Madeira. The name Loicos is derived from the phrase Nezi Loicos "Isle of Loico", from the Gallaecian phrase **Enistī Lugudekos "Island of Lugudes". In Latin, it was called Insula Lu(g)udeci.

3. ATL Tenerife. It is derived from the Latin name for the island (Nivaria).

4. ATL Fuerteventura. It is derived from the Latin name for the island (Planasia).