For my first topic, I'll be talking about allophony (Did you know it's pronounced /əˈlɑfəni/? I didn't until today) between voiced lateral and central liquids like [l], [r] and [ɾ], and sometimes even the plosive [d], in different languages. A number of languages have a single liquid phoneme that can be realized as either central or lateral; sometimes this is conditioned by the phonetic environment.

We'll start out with some examples from the Bantu languages.

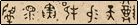

In

Luganda, /l/ usually has the allophone /ɾ/ after /e/, /eː/, /i/ or /iː/. This could be analysed as /l/->[ɾ]/_[+front] or /l/->[ɾ]/_[+close][-rounded]. However, these two allophones can also substitute for one another freely in all contexts. When prenasalized (preceded by a homorganic syllabic nasal), it merges with the usually distinct phoneme /d/. When geminated, it is realized as /dː/, the same as the geminate of /d/.

Sesotho has a phonemic plosive inventory of /pʼ pʰ b tʼ tʰ kʼ kʰ/.

However, /l/ is realized as [d] before a high vowel /i/ or /u/. This is believed to have developed from [ɽ]. This pattern of allophony also exists in the related language Tswana, which also has a distinct alveolar trill phoneme /r/. Sesotho also had /r/ historically, but the modern realization of this phoneme tends to be /ʀ/, possibly due to French influence.

Many Polynesian languages have only one liquid. In

Samoan, /l/ is generally pronounced as a central flap [ɾ] when it is both following a back vowel /a, o, u/ and preceding the high front vowel /i/.

The language that most famously has l~r allophony is probably

Japanese. Japanese /r/ may be realized in a variety of ways: as a lateral approximant, a lateral or central flap, or sometimes even an alveolar trill. It tends to be realized as a central flap [ɾ] most often before /i/ and /j/, and it is most likely to be realized as a lateral approximant /l/ before /o/. In general, though, the two sounds are in free variation with each other and other realizations of the phoneme.

In the nearby language

Korean, /l/ is realized intervocalically as an alveolar flap [ɾ], and as the lateral approximant [l] or [ɭ] at the end of a syllable or when following another /l/. In South Korea, this sound cannot occur at the start of a word or directly following another consonant: historical /l/ in these positions generally merged with /n/ (followed by later simplification of /nj/ and /ni/ to /j/ and /i/). However, in the sequence /nl/, the n is assimilated with the result of a geminate /ll/. Loanwords from English have now reintroduced the phoneme word-initially, where it exhibits free variation between [ɾ] and [l].

Hopefully some of these examples will appeal to you when you are making your language's phonology, or inspire you to create your own pattern of allophony involving these sounds.